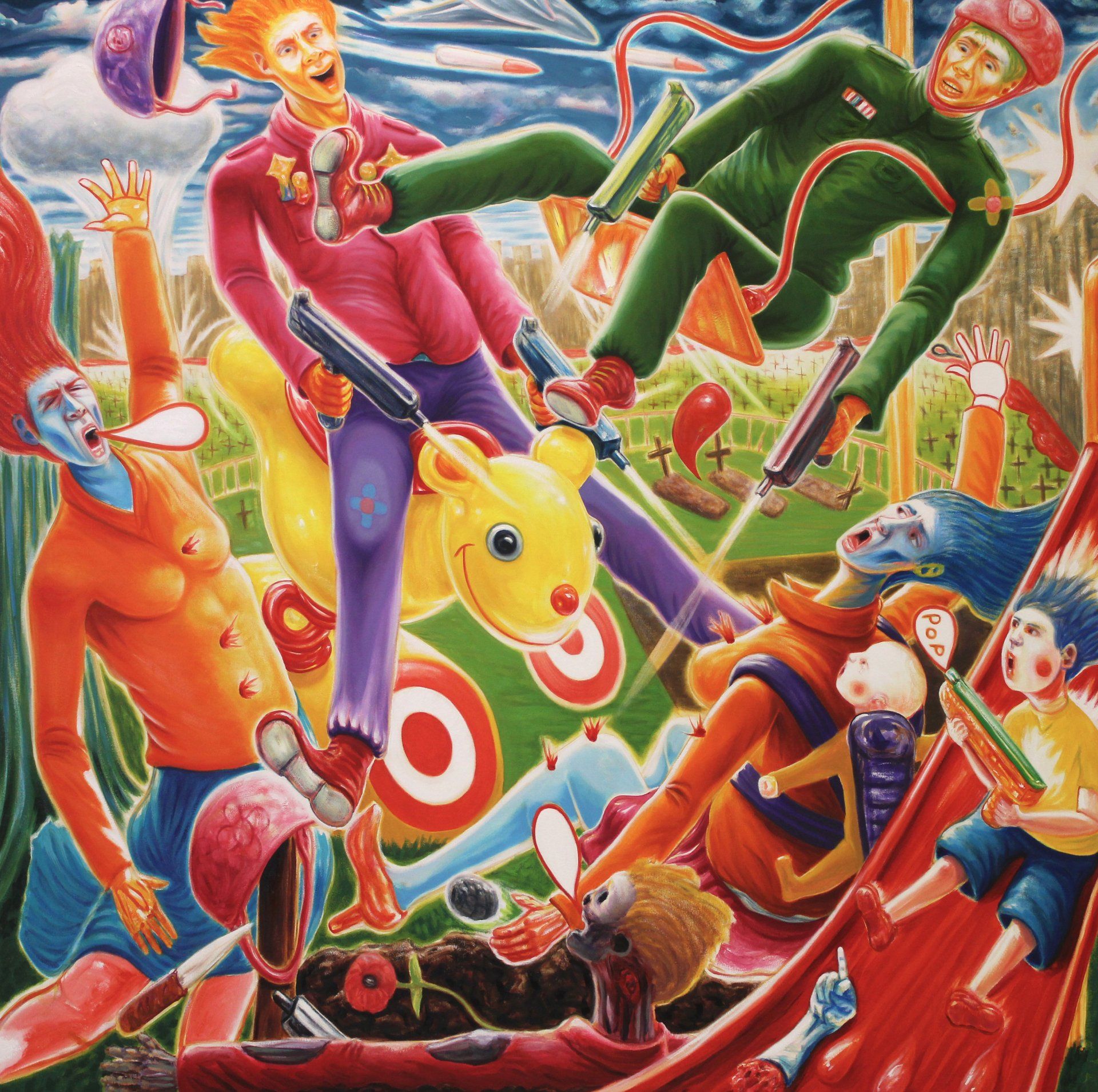

Painting. A critical view.

Art history, like every other discipline at the present time, is undergoing a transformation. Now that the outstanding works of previous ages have been inventoried, and the attempt has been made to classify them on the basis of their external characteristics, now that formal analogies have been discovered between works remote from each other in time or space, and a symbolic interpretation of figurative signs has been worked out, new types of investigation are being attempted. A closer link is sought, for example, between art and its social context; and by restating in more complex terms the old problem of form and content, the notion of the sign-symbol is superseded and an approach made to the work's specific value as a created thing. This evolution within one discipline cannot, of course, be separated from the changes taking place in other forms of criticism. Even less readily can it be isolated from the evolution of art itself.

The historian and the critic also take a hand in the game. They belong to their own age, and the contribution they can make does not repose upon some set of absolute values-this would locate them somewhere outside the world-but upon their skill in uncovering contemporary viewpoints. Each generation of critics comes upon new values in past and present, and criticism can claim to exercise a positive function to the extent that it aids in working out new aesthetic values that attract living artists.

Winckelmann's criticism played an influential part in the development of philosophy, poetics and even politics, during the Enlightenment; and Sainte-Beuve ranks no less high than Musset when one seeks to define romanticism. In any firmly established historical perspective, it is an easy matter to discern and evaluate the part played by criticism. Only those works and critical opinions survive that have become common property, and have served as the base for later developments-the be- wildering chaos of day-to-day occurrences has yielded to a few ordered series. But, for our own time, it seems altogether arbitrary to try to predict what posterity's simplifying judgment will be. And what counts above all, one feels, is that this whole upsurge of life should not go unperceived. In this connection, the duties of the artist are quite unlike the critics. The former is entitled to push ahead uncompromisingly, whereas the latter must situate the artist in an ideological network whose relativism knows no bounds so that he may assign him a place in his own immediate setting and in history. Hence the violence and seeming incoherence of the views expressed on contemporary art. However well aware he may be of the absolute character of artistic creation, however firmly persuaded that the artist has the right to intransigence, the critic for his part necessarily envisages a multiplicity of possible solutions, even though he may feel a marked inclination to support one of them and repudiate the rest. Actually, criticism ends in many instances with the voicing of a preference and is often indistinguishable from eclecticism. This throws considerable light on the motivations of critics and historians, in the attitude to contemporary art most frequently adopted since the turn of the century. Straining for objectivity, fearful of seeing too much in forms of art that will later turn out to have been sterile, fancying themselves as prophets rather than as the analysts of their own time, they have presented panoramas of modem art and eschewed all critical judgment. They have sought to extrapolate on the basis of the past rather than to discover the connections between a living, speculative approach to artistic activity and the general tendencies, in our day, of scientific research. They have looked for enduring values, and have done much less to discern anything strikingly new in the creation of forms, with values that are questionable, perhaps, but which may eventually give rise to other works. Some artists and schools have had their perfervid champions, nevertheless. Critics have supported, each in its turn, the "cause" of Fauves and expressionists, of cubists and of abstract art. But some- where between a partisan attitude and an inchoate eclecticism that generally masks an absence of taste, it is not easy to say precisely where the real critic should take his stand. Some conclusions may be drawn, however, if we first reflect on the conditions in which artistic creativity must currently function. Present-day painting is characterised by the extraordinarily important changes that have occurred both in painting technique and in the treatment of figures. Every age witnesses a clash of generations, those who cling to the established forms confronting others who prefer innovation. But the gap that separates tradition and novelty is not always equally great. In the last fifty years, it is un- deniable that the very notion of what painting is has undergone a change. The difficulty lies in distinguishing between mere arbitrary fantasy and a proper obeisance to the spirit of the time. Art historians at the beginning of the century were ill-equipped to make this distinction.

The outstanding theoreticians of the preceding generation, if we accept that the dogma of art is timeless, artists are connected with each other by the cyclical the artist is but the instrument that concretises a kind of evolving force; a kind of anonymous art history might be conceived which would reflect only superficially the specific needs of each age. Art is identical to the formal ideal. The artist participates in this fundamental social activity only by identifying himself with a moment in the successive phases of the life of forms; the accidents of his personal existence do not concern him. History. Conversely, the work exists only as a revelation of the artist's personality. It is the product of an activity irreducible to any other. There is no history of art, apart from the personality of the artists. There are no constraining cycles. Man is an individual and he is free. What he creates is no mere contingent thing, but partakes of the absolute of the human consciousness reflecting the universe at a given moment, and this via the individual man. There is no history transcending individualities. Art and man are freedom, in a stable universe that they play no part in shaping. It is not too much to say that all the theories and undertakings of the last fifty years go back to one or the other of these doctrinal attitudes. History has been written by looking at contemporary painting either as the last link, the destructive phase of the old order, or as the result of the free imaginative activity of some dream-bearing individuals. Either the works are presented as reflecting the multiplicity of the doctrines incarnated in the "schools" (fauvism, expressionism, cubism, futurism), or a few "poets" are extracted from their surroundings (Chagall, Miro, perhaps even Picasso, for his so-called "sensible" periods). Thus a rigid and negative view of the art of our time is built up, or, alternatively, isolated factors are magnified into a poetics of the eternally human. As a consequence, any artist today would be obliged either to circumvent or to dislocate established forms, unless, of course, an artist's vision is exemplified by their immediate social circumstances, and pursued through autoethnographic means.